The fire that burned through more than 50 percent of Henry W. Coe State Park south of San Jose over the past week may have pumped huge amounts of soot into the air and been a headache for firefighters, but the animals in the park and its scenic landscape weren't wiped out.

From an environmental standpoint, the blaze - which was 95 percent contained Sunday night - has been a good thing, a natural event that has occurred in the area for thousands of years, several wildlife experts said Sunday.

"The park is not destroyed. The fire is actually beneficial to the environment," said Stuart Organo, supervising ranger at Coe.

"Next year after the rains have fallen in the spring, there is going to be more grass and vegetation for deer and other animals to browse on," Organo said.

Park rangers so far have no reports of major wildlife die-offs, he said. Many of the large animals, from black-tailed deer to tule elk to mountain lions, ran away from the flames to other areas in the vast Diablo Mountain Range and will return, he said.

Some smaller, slower-moving animals like skunks or raccoons, probably were killed. But others, like ground squirrels or snakes, burrow underground as flames pass over and should have survived, experts said. Meanwhile, thousands of acres of thick chaparral and dead brush have been thinned out, allowing new grasses and wildflowers to grow, which will provide more food soon for wildlife, said Henry Coletto, who worked 40 years

"We had Bambi and Smokey Bear. They made us all think fire was really bad for wildlife," Coletto said.

"It's important to be careful with your campfire," he added, "but for the most part, fire is a good thing for the landscape as long as it doesn't burn houses down."

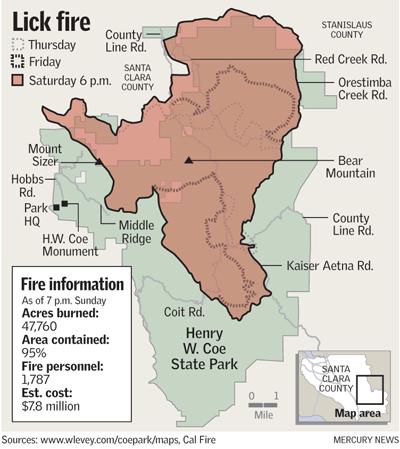

By 7 p.m. Sunday, the blaze, called the Lick Fire because of its proximity to Lick Observatory, had burned 47,760 acres. Nearly all of it was within the 88,000-acre Henry W. Coe State Park, an expansive landscape of oak woodlands and steep, dry chaparral.

The fire started last Monday. There were no fatalities or serious injuries. Apart from three hunting cabins and two barns, the area that burned is so remote in the hills east of Morgan Hill that no homes were destroyed, said Chief Frank Kemper of Cal Fire, formerly known as the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

"Today the weather has been working with us," Kemper said. "We've had cooler temperatures. Crews are working hard."

Kemper said that the 1,787 firefighters working on the blaze are going to be sent home in the next several days. Full containment - the practice of surrounding the burned area with fire lines from ranch roads or cut anew by bulldozers - was expected by today. Some fire crews will remain for a few more days to mop up the last embers and hot spots, he said.

Kemper said Cal Fire still is not releasing the name of the person who started the fire, which he said was not deliberate. Fighting it so far has cost taxpayers $7.8 million.

"Once the investigation is complete we'll make the name public," he said.

Fire has always been part of the park's landscape. State parks officials burn about 1,000 acres there every year using controlled burns to thin the chaparral and return the condition of the land to its natural cycles, Organo said.

Until the Gold Rush, the landscape would have burned about every 10 years from lightning strikes. Ohlones and other Indians who lived in the area before that also regularly burned large areas every fall.

"They did burning as well," said Teddy Goodrich, a Gilroy historian. "It made the small game like rabbits and squirrels more visible, and it made for better wildflowers and bulbs, which they ate the next spring."

Coletto, the former game warden, said that had the fire burned early in the summer, wildlife would have suffered more. That's because there would have been a long wait before cool weather began to regrow grasses and other plants.

But now, with coastal fog already creeping in during the mornings, and winter rains on the way, new plants

sprout in a matter of weeks, he said. The removal of thick chamise and manzanita will allow more sunlight to sprout a wide variety of native grasses and flowers, and will allow wildlife to pass through more easily.Some trees, like ponderosa and gray pines, require fire to open their cones and release seeds, Coletto said. And the ash will fertilize the ground.

"It looks bad right now, but the wildflowers, the grasses, the vegetation will pop right back," he said.

"`That ash is full of nitrogen," he said. "Every plant sucks it up. Because there haven't been fires up there for so long, there are nitrogen deficits. "

In fact, Coletto said, there may be more environmental damage - erosion - from the fire lines cut by bulldozers than from the fire itself.

Goodrich said that the last huge fire in the park area occurred in the late 1930s.

Because the area is so remote, motorists on Highway 101 won't be able to see the black areas.

"Next spring is going to be awesome for wildflowers," Organo said.

To see the burned area "you're going to have to hike two or three miles from park headquarters," he said. "You gotta remember, this is a really big park."

Contact Paul Rogers at progers@mercurynews.com or (408) 920-5045.

RSS

RSS